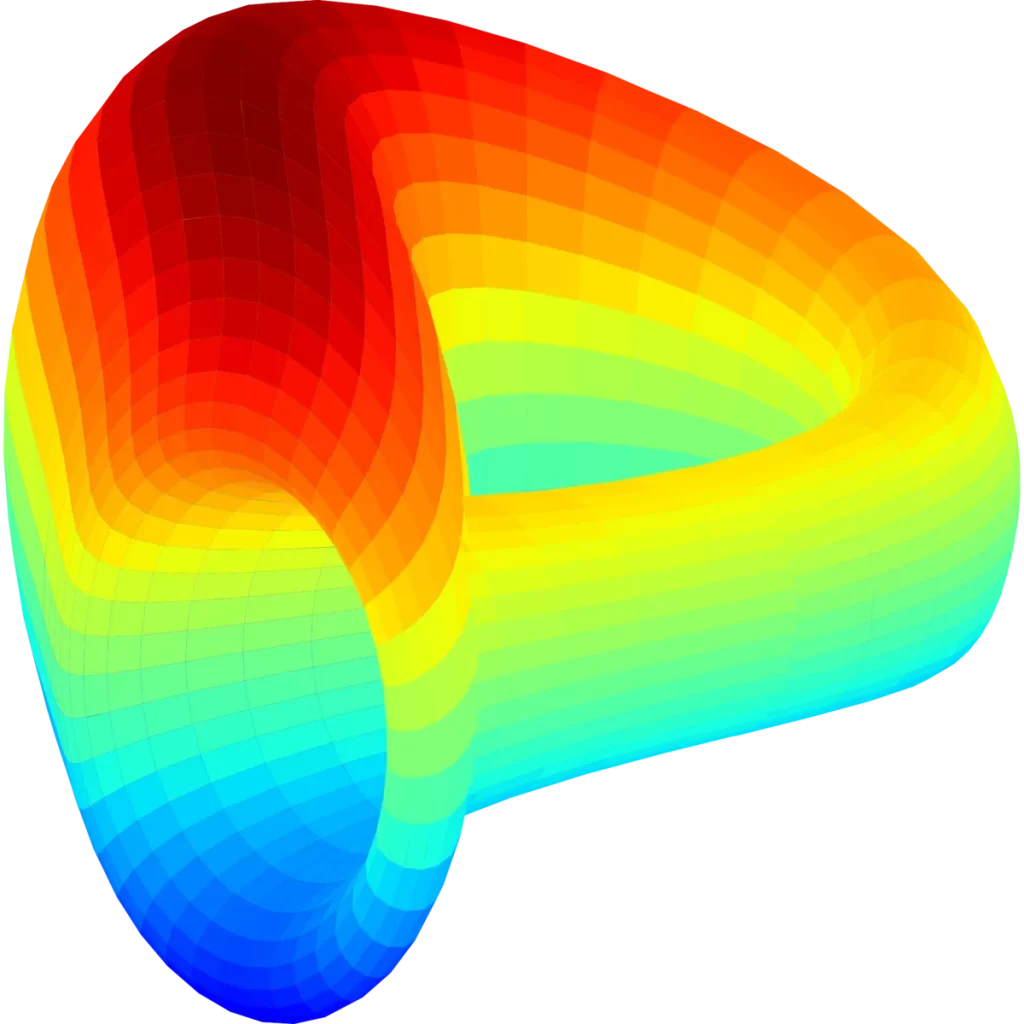

The hierarchy of value capture is the axis along which protocols and the tokenomic mechanisms they employ can be ordered.

Protocols face a challenge in navigating this hierarchy when designing their value capture: mechanisms in the hierarchy of value capture can be ordered simultaneously as ascending in value capture, and descending in defensibility.

In essence, the more value a protocol captures, the less defensible it is.

This phenomenon epitomizes the tradeoffs between the first two principles of tokenomics: value capture, and utility; it will be helpful to understand a bit about these concepts before reading further.

Utility and value capture have tradeoffs because of their interdependence – the maximum value you can capture is the total value you create. As more value is captured, less is left for consumers.

Value creation, or utility, and value capture in crypto protocols resemble those of traditional companies, but they are not perfect analogs.

In a traditional business, value creation is the total value ascribed by consumers to a product or service; value is most frequently captured through profit, a percentage of the value created.

In crypto, utility is the same – the value created by a protocol, for users, but value capture is often different.

Value can be captured in more ways than in traditional businesses because of the types of tokens that are able to be created, and the underlying utility and flexibility of the blockchain back end.

But for both crypto protocols and traditional companies, the ability to capture value long-term is proportional to two things: value creation and defensibility.

Defensibility

Defensibility is the competitive advantage of a protocol. It describes how much value can be sustainably captured before comparable utility is offered by a competitor.

The more defensible a protocol, the more value it can capture, and the more overtly it can do so.

Maximizing defensibility results in a monopoly.

In Peter Thiel’s famous talk at Stanford, he describes why you want to have a monopoly in your industry – monopolies can capture nearly all of the value they create.

It’s difficult to have a monopoly in crypto, as it’s hard to build defensibility – how do you compete when your competition knows your secrets?

Still, there are various ways to build defensibility, and the more defensibility you have, the more value you can capture.

Tokenomic leverage

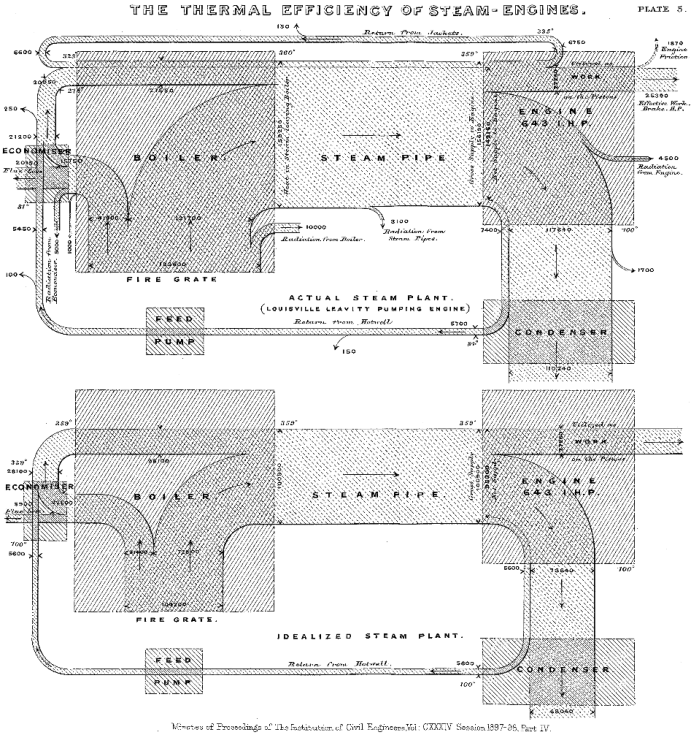

The ratio of value captured to value created is called tokenomic leverage. Higher tokenomic leverage in a tokenomic mechanism or protocol overall is analogous to higher profit margins in a traditional business.

Tokenomic mechanisms further up the hierarchy have higher leverage. And it’s possible to have a tokenomic leverage greater than 1 – indicating more value is being captured than created.

Users of Synthetix can create sAssets – synthetic TradFi assets collateralized by several times their dollar value in SNX tokens.

Synthetix governance decides this collateralization requirement, but it generally stays between 300% and 500%.

This means that SNX will necessarily be worth 3-5 times the value of all necessary sAssets.

So the tokenomic leverage of this mechanism in the protocol is between 3 and 5, depending on the current collateral requirement.

Synthetix’s collateralization mechanism introduces economic security issues only mitigated by active management of the c-ratio, and heavy inflation. As a result, Synthetix has begun to pivot its design toward other tokenomic mechanisms with lower value capture – but not for fear of competition.

Synthetix still has a monopoly on synthetic assets in the Ethereum ecosystem. If economic security were not also a concern, SNX could retain its inordinate tokenomic leverage.

This is only possible because the protocol has a monopoly; higher tokenomic leverage requires extreme defensibility.

Capturing value creatively

In traditional businesses, profit comes at the consumer’s expense – there is a direct tradeoff between value creation and value capture.

McDonald’s Corporation, however, is a notable exception.

McDonald’s share price has grown nearly 1,000,000% in its 58-year history – and they didn’t do it charging $12 a burger.

McDonald’s is a real estate company – it accumulates properties and rents them out to franchisees, selling them when appropriate.

This alternative method of value capture enables McDonald’s to subsidize their actual product – burgers and fries – crippling the competition and making for a defensible business, while still capturing value for shareholders.

McDonald’s alternative means of monetization is a prototype of mechanism design, the most crucial aspect of tokenomics.

Mechanism design is the construction of sets of incentives to create desired outcomes. Good mechanism design follows the principles of tokenomics, which are the focus of the demand-side tokenomics framework.

Curve’s CRV

Curve gets a lot of press, both good and bad for its vote-escrowed or ve tokenomics.

But Curve’s ve tokenomics are only a part of its creative value capture methods.

Like McDonald’s, Curve subsidizes their product, trading, with their alternative method of value capture.

Curve’s captures value through bribes – the more bribes being paid to LP’s, the more demand there is for CRV.

The subsidization of trading fees is also proportional to the value of bribes paid to LP’s.

Systemic consequences

Navigating the hierarchy of value capture is a stumbling block for most protocols designing their tokenomics.

Failing to see the problem clearly, many protocols overcompensate in capturing value.

When a protocol captures too much value, attempting to use their own token as a medium of exchange for example, they alienate users, enabling their competitors to copy their protocol without using a native token, capturing value through fees or another tokenomic mechanism with tokenomic leverage.

If a protocol captures too little, they lose out on the opportunity to capture value at all, and doom any competitors to the same fate.

Uniswap’s failure to capture value from the start led to the need for Curve to capture value creatively in the first place.

But in reality, Curve didn’t only capture value creatively.

Curve had to create additional utility to compete with Uniswap, because Uniswap had set the AMM market’s barrier to entry at zero value capture or less.

Subsequent AMMs capture even less value, issuing evermore inflationary tokens to subsidize their operations; as a result of Uniswap’s initial failure, all future AMMs are forced to capture negative value just to compete.

And while Curve’s innovation of ve tokenomics was clever, Curve would have been able to capture more value, with better margins had Uniswap captured value as well.

Avoid at all FOSS

Arguably the worst fate for crypto would be to follow in the footsteps of the FOSS (free, open-source software) movement.

Linux was built by similarly ideologically motivated developers who believed, as a faction of crypto does, that software should be free.

The result was unsurprising: software with poor UX, which most people hate.

Linux has been relegated to a small percentage of computer users, while competitors Apple and Microsoft were left to capture inordinate amounts of value extractively because of the duopoly they were left with.

Crypto has a unique opportunity to do open-source right; in Linux’s day, the internet had no native currency – no way to transfer value, charge microtransactions, or accrue value to native assets.

Now, there is more opportunity than ever to create valuable, yet open-source software and get paid for it.

The study of that monetization is called tokenomics.

Conclusion

Tokenomics can be hard to get right, and there’s a lot riding on them, both for your protocol and for the broader industry.

We walk founders and developers through these important questions with the Demand-Side Tokenomics framework – a series of questions and worksheets designed to evoke the optimal design for your protocol based on the principles of tokenomics.

If you’re building a protocol and would like help, or a step-by-step guide on how to design for optimal utility, token price, and longevity of the protocol, reach out to us and tell us what you’re building.